평화를 위한 풍선, 우리는 왜 풍선을 북한에 띄우나?

평화를 위한 풍선, 우리는 왜 풍선을 북한에 띄우나?

북한에 풍선을 날려 보내는 일은 절대 지루한 일이 아니지만, 특히 요즘이야말로 풍선을 날리기엔 흥미로운 시점이다. “풍선 날리지 말고 좀 기다려줄 수 있나요?” 이 말이 바로 필자가 반복해서 듣는 질문이고 정부 당국자, 경찰, 매체, 페이스북 댓글, 심지어 친구들로부터 불만스럽게, 그리고 긴급하게 듣는 말이다. “당신이 이 평화 협상 절차보다 더 중요한 사람이야?”, “우리 모두를 위험하게 만든다는 사실을 모르고 있나?”, “당신의 그 편파적인 목적이 모두의 평화보다 더 중요해?”

들리는 바에 의하면, 통일부까지도 풍선을 날리는 어떤 단체들에 다른 인권 활동으로 전환하면 지원하겠다고 한다. 통일부가 판단하기에 최근 열린 평화회담의 분위기를 망치지 않는 그런 활동들을 말이다. 모두가 남북 사이에 이루어진 긍정적인 협약과 상호 존중의 분위기에 감명을 받은 듯 보인다. 풍선 날리는 일을 하는 사람들을 뺀 모두가 말이다.

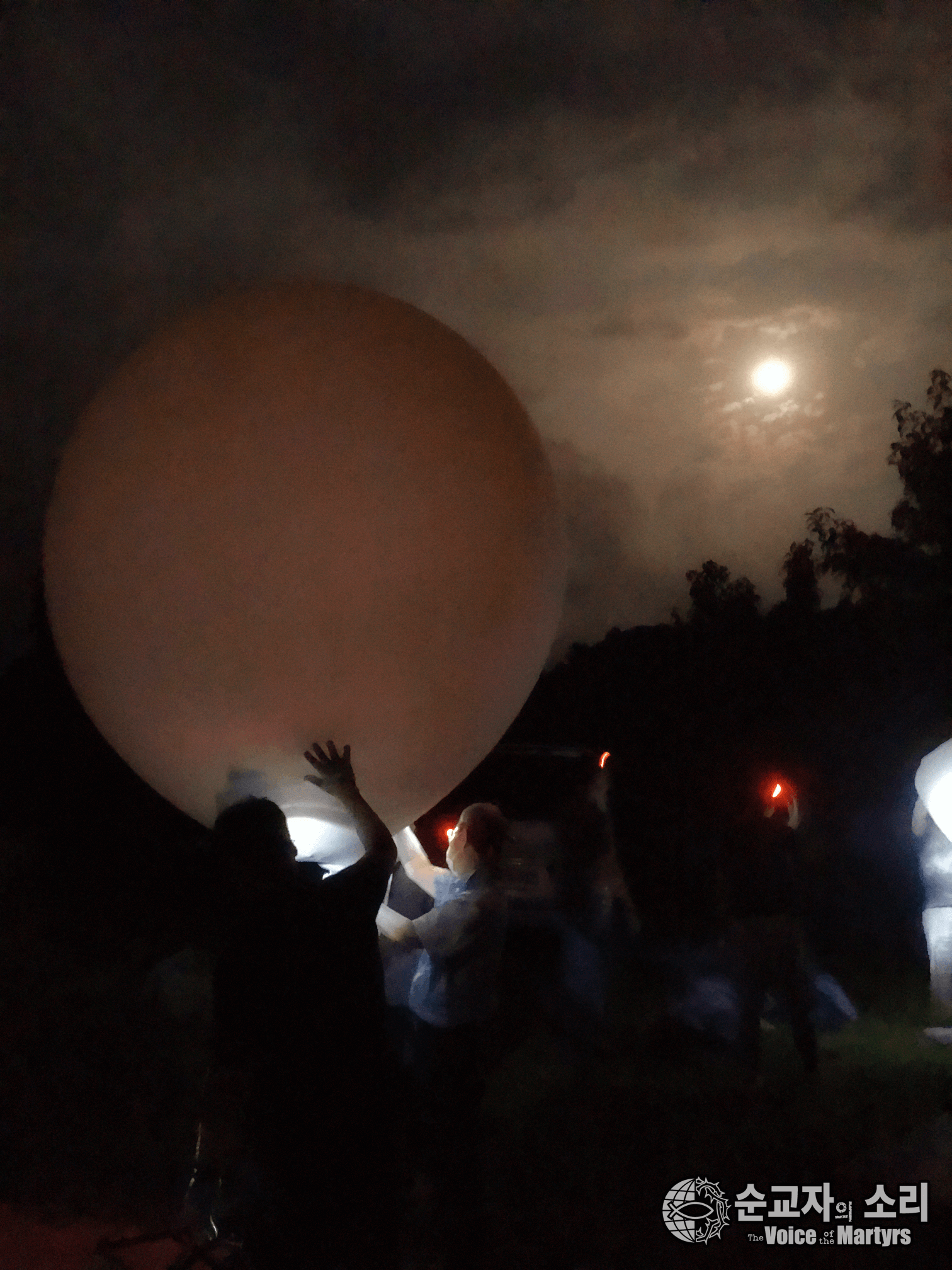

분명히 말하건대, 내가 풍선을 날리는 모든 사람을 대변할 수는 없다. 날려 보내는 풍선의 양으로 따지면 우리 단체, 즉 한국 순교자의 소리는 풍선 사역에서 ‘거목’임에 분명하지만, 대북 풍선을 날리는 다른 단체들과 우리 단체의 공통점은 거의 없다. 우리는 인권에 관련된 대북 전단이 아닌, 오직 성경만 날려 보낸다. 이 성경은 바로 북한 정부가 출판한 번역본으로, 북한 정부가 주장하는 바에 따르면 북한 헌법에 의해 모든 북한 주민들이 합법적으로 읽을 수 있는 성경책이다. 우리는 풍선을 날릴 때마다 항상 경찰에게 알리지만 대중 매체들에는 절대 알리지 않는다. 항상 밤에 풍선을 날리고 인적이 드문 외딴 곳에서 작업을 한다. 고가의 최첨단 기술을 사용해 풍선과 성경책들이 안전하게, 문제를 일으키지 않고 북한으로 유입될 수 있게 한다. 이 기술들은 고도의 컴퓨터 모델링과 GPS 추적장치, 또한 기상 관측이 가능한 풍선(크기가 작아 레이더망에 잡히지 않으며, 착륙하지 않고 흔적 없이 공중에서 터지는)에 사용되는 기술들이다. 올해부터는 헬륨가스만 사용하고, 훨씬 더 저렴하며 논란이 많은 수소는 사용하지 않는다.

분명히 이 풍선들은 효과가 있다. 북한인권기록보존소의 “2015년 북한종교자유백서”에 따르면, 북한에 있을 때 성경책을 보았다는 북한 주민들의 수가 2000년 당시 0%에서 2014년에는 7.6%로 늘어났다. 그리고 이건 우리가 풍선으로 보낸 성경책 때문만은 아니다. 어쨌든, 순교자의 소리와 다른 단체들이 다수의 경로로 북한에 성경을 보내고 있다. 이러한 다른 수단을 다 합쳐도 우리가 매년 4만 권씩 10년 이상 보내왔던 성경책들의 효과에는 턱없이 미치지 못한다.

그럼에도 불구하고, 당신이 이렇게 묻는다 해도 이해할 수 있다. ‘단지 기독교인들이 북한 주민들을 전도하고, 탈북자들이 북한 정부에 항의할 목적으로 평화 과정을 위태롭게 해야만 하는가?’ ‘표현의 자유와 종교의 자유가 아무리 중요하다지만, 긴급한 국가의 이익을 해칠 만큼 중요한 것인가?’

이런 방식으로 전형적인 논쟁이 진행되고, 결국 풍선을 날리는 사람들의 편에는 적은 수의 사람들만 남아있게 된다. 그러나, 진짜 문제는 이 논쟁이 진행되는 방식 그 자체일지도 모른다. “풍선 날리지 말고 좀 기다려줄 수 있어요?” 하는 질문에는 “당신은 왜 이 평화협상 절차를 존중하고 신뢰하지 못해요?”라는 의미가 숨어있다. 그러나 정부 간 평화협상 절차를 진심으로 존중하고 당당하게 행동하면서, 평화에 관한 우리의 이해와 실천을 충분히 살릴 수 있다.

달리 말하면, 평화는 매우 중요하고 너무 큰 사안이기 때문에 정부가 홀로 이루어 낼 수 없는 것이다. 문재인 대통령 뒤에DMZ 남쪽에 사는 모든 이들이 줄줄이 따라가고, 김정은 뒤에 DMZ 북쪽에 사는 모든 이들이 줄줄이 따라와서 누구도 그 행렬에 벗어날 수 없는 그 순간에 만들어지는, 그런 종류의 평화가 있다. 그러나 그것은 사전에 계획된, 제도화된 평화이다. 정부가 공급한 깃발들이 휘날리고, 소셜 미디어에 적합한 사진들을 찍고, 남북 정부가 편한 그들만의 속도대로 그들의 편의에 맞춰 서로의 관계를 쌓기 위해 스포츠나 문화를 교류함으로써 말이다. 역사적으로 살펴보면, 선언문에 의한 평화는 무너지기 쉽고, 빈약하며, 부자연스럽고, 그 생명을 유지하기 위해 연명 조치가 필요하며, 그것을 보호하고 보존하기 위해 물리적인 힘이 항상 필요하다.

그와는 반대로, 우리는 사람들이 베를린 장벽을 오르던 장면을 기억함으로써, 분열된 사람들을 하나로 만드는 진정한 평화는 보통 선언문을 통해서가 아닌, 다수의 사람에 의해 이루어진다는 사실을 상기해야 한다. 평화협상 절차에 있어 정부의 역할은 평화를 만들어 내는 것도, 평화를 성취하는 것도, 평화를 정의하는 것도, 평화를 예정하는 것도, 평화를 조직하는 것도 아니라, 다만 평화를 저해하는 행위를 중단하는 것이다. 스포츠와 문화 교류를 통해 나누는 사랑이나, 아시아 횡단 철도에 대한 환상, 또는 서로가 가진 전쟁에 대한 반감을 확인하는 것으로 남북한의 두 나라가 서로 깊이 연결되지 않는다. 간단히 말하자면, 평화는 지극히 평범한 한국 사람들만의 것이다. 이 나라 사람들은 그들 사이의 소통에 있어 시중들어 줄 보호자가 필요 없으며, 서로를 다시 소개해줘야 할 필요도 없다. 남한과 북한의 젊은 세대들이 가지고 있는 서로를 향한 거리감에도 불구하고, 남한과 북한 주민들 사이에는 충분히 자연스러운 유대감이 아직도 남아있으며 남북 정부가 (전쟁으로) 서로를 날려버리지 않겠다고 서약한다면, 평범한 한국 사람들은 이 평화를 이룩하는 핵심적인 과정, 즉 시간이 오래 걸리고, 성취하기 어려우며, 값비싼 대가를 치러야 하는 이 작업을 어떻게 시작해야 하는지 본능적으로 알 것이다. 이것은 남한과 북한이 공유하고 있는 유교 문화의 유익 중 하나이고, 인공적인 방해물(정부가 만들어 놓고 유지하고 있었던)이 제거되었을 때 작동되는 사람의 자연스러운 본능 중 하나이다.

이 글은 로널드 레이건이 서독의 브란덴부르크 문에서 고르바초프에게 “이 장벽을 허무시오.”1라고 말한 것처럼 말로 평화를 이루자는 순진한 제의가 아니다. 흥미롭게도, 적어도 한번은 이 순진한 제의로 평화가 일어났지만 말이다. 대신, 이 글은 정부의 노력을 그저 지원하기보다, 우리가 무언가를 함으로써 평화를 이루려는 정부의 역할을 진심으로 존경할 수 있다는 선언이다. 우리는 정부가 하는 것과는 다른 방법으로 평화를 이루는 일에 참여할 수 있다. 우리는 정부가 우리에게 평화절차에 참여하는 자신들만의 방법을 알려주기까지 기다리면 안 된다. 사실 평화라는 총체적 목표에 가장 존경을 표할 방법은 우리 각자가 평화를 위한 우리만의 독특한 개인적 기여를 하는 것이다. 정부는 우리의 기여를 좋아하거나 좋아하지 않을 수 있다. 이해하거나 이해하지 못할 수도 있다. 자신들만의 평화협정절차에 딱 들어맞다거나 그렇지 않다고 할 수 있다. 그래도 괜찮다.

진정한 평화는 수많은 관중이 함께하는 스포츠도, 일방적인 노력도, 차례로 공연되는 3막짜리 연극도 아니다. 진정한 평화는 정부가 협상해서 이루는 것이 아니라, 정부가 인식하는 것이다. 진정한 평화는 발발하는 것이다. 전쟁이 발발하는 것과 비슷한 양상으로 말이다. 전쟁이란, 우리 몸 안의 장기들이 문제를 일으키는 것처럼 이 사회에서 기능하는 각 장기가 동시다발적으로 파손된 상태이다. 이처럼 진정한 평화도 어떤 한 장기의 단독적인 제어와 조직화가 만들어낼 수 없는, 사회 각 장기의 동시다발적인 회복을 의미한다. 각 장기는 평화를 이루는데 있어 각자의 독특한 역할을 가지고 함께 기능하고 있다. 또한, 평화협상과정에 참여하는 이들은 이 평화야말로 그 어떤 하나의 장기가 혼자서 이루어 낼 수 없는, 그 어떤 장기도 앞장서서 이루어 낼 수 없는 것임을 알아야 하며, 이 사실을 받아들이기에 충분히 겸손해야 하고, 이 과정이 일어날 수 있게 충분히 지혜로워야 한다. 기독교인들은 이렇게 말할 것이다. 평화가 하나님의 때에 비공식적인 수단을 통해 이루어진다고 말이다. 그러나 당신이 가진 신앙의 배경과 관계없이, 평화는 정부로부터가 아닌, 한 사회 전체에 걸쳐 이루어졌다는 사실을 역사가 보여준다. 그 누구도 이것을 이루어내지 못했다. 대통령들까지도 말이다.

우리 순교자의 소리가 풍선에 성경을 실어 날려 보내는 이유는 북한 주민들을 전도하려는 것이 아니다. 다만 평화협상 과정에 기여하기 위한 노력의 일환이다. 우리는 북한 주민 개개인의 인간다운 삶에 대한 다른 평가 기준을 발전시키려는 북한 지하교인들의 노력을 지원하는 것이다. 성경은 우리 각자가 정부에 충성스럽고 유용한 인간이기 때문이 아니라 단지 하나님의 형상, 즉 정부로부터 승인될 수도, 보류될 수도 없으며, 양도될 수 없는 상태로 만들어졌기 때문에 인간적인 대우를 받는 것이 당연하다고 말한다. 우리는 10년이 넘는 시간 동안 조심스럽게, 북한 주민들의 언어로 된 메시지이자 북한 정부가 번역하고 보호하는 이 메시지를 북한으로 날려 보내 왔다. 남한 정부의 법(그리고 처벌)에 온전히 따르며, 김정일이 사망했을 때에도, 천안함 사건 때에도, 제1연평해전 때에도 우리는 이 메시지를 날려보냈다. 그러나 북한 내에, 그리고 북한 주변 지역에 있는 다양하고 널리 퍼져있는 우리의 연락망이 쉽게 증명해 주듯, 평범한 북한 주민들에게 다다른 이 성경책들은 많은 사람의 마음에 삶의 의미와 용서, 그리고 평화를 가져다주었다.

기독교인들은 아마 남북 정부가 꿈꾸는 평화와는 다른 평화를 상상하겠지만, 동시다발적으로 일어나는 평화적인 노력을 제거함으로써 정부의 평화협상 절차가 강화되고 보호될 것으로 생각하는 것은 매우 이상한 일이다. 풍선을 날리는 다른 사람들을 대신해서 말하자면, 이런 평화적인 노력에는 평화 시위 또한 포함된다. 역사를 보면, 이런 평화 시위는 스포츠 및 문화교류, 대륙 간 철도건설을 위한 계획만큼 시민 사회에 평화를 가져다주고 유지해주었다. 풍선을 날리는 대북단체들의 전단 내용이 가끔 과장되고 투박할지도 모르나, 이 전단을 “대북전단”, 즉 북한에 반(反) 하는 전단이라고 표현하는 것은, 애석하게도 중립적이라고 알려진 세계적인 뉴스들이 이런 식으로 표현하는데, 이것은 모든 북한 주민들을 그들의 지도자와 동일시함으로써 이들을 정치적 논쟁거리로 삼는 지독한 오류를 범하는 것이다. 남북 관계의 이러한 정치 이슈화는 분명 평화에 가장 큰 걸림돌이 된다. (아니면, 적어도 이러한 정치 이슈화를 극복하는 것이 평화를 이루는데 가장 큰 희망을 가져다 줄 것이다.)

풍선을 날리는 사람들은 남한과 북한의 정부가 계속 유지해온 장벽을 극복하고 평범한 남북한 사람끼리 서로 직접 대화하기 위해 풍선을 날린다. 평범한 이들이 DMZ를 만든 것이 아니다. 정부가 만든 것이다. DMZ는 서로를 믿지 못하는 평범한 이들이 만든 것이 아니다. 이것은 평범한 이들이 정부를 지나치게 믿고, 정부에게 지나치게 맡겼기에 만들어진 결과물이다. 다시 말해, 평범한 남북한 사람들 사이의 관계가 정치적 논쟁거리로 되었음을 DMZ는 보여준다. 이렇게 정치 이슈화가 되고, 심지어 변경된 형태(즉, 세심히 관리되고 연출된 행사나 교류를 통해 북한 사람과 남한 사람으서 상호작용하는 형태)로 유지되는 평화협상 과정은, 최악의 경우에는 실패할 것이 뻔하고, 기껏해야 한 민족으로서 인간으로서 가족으로서 서로 직접 소통하는 것이 평화라고 주장하는 남북한 사람들에게 어느 시점에 전복될 것이 분명하다. 로버트 프로스트(Robert Frost)는 그의 시 ‘담장 고치기’에서 “담장을 싫어하는 무엇이 있어, 그 아래 언 땅을 부풀게 하여…”라고 썼다. ‘그 아래 언 땅을 부풀게 하는’ 인권단체의 전단지들은 때로 보고 싶지 않을 수 있지만, 결국 그 담을 부순다. 특히, 그 담장이 담장 반대편에 있는 당신의 사랑하는 사람들과 멀리 떨어져 있게 한다면 말이다.

남북한 정부는 평화를 이루는 과정에서 자신들이 해야 할 역할이 있지만, 평화를 이뤄내고 서로 소통할 수 있는 우리의 수단들을 정부가 독점하게 허용해서는 안 된다. 그들이 주기적으로 평화협상 절차를 위해 노력하기 전이든, 노력하고 있는 중이든, 아니면 노력한 후에라도 말이다. 남한과 북한의 정부는 평화를 이루는 과정에서 자신들이 해야 할 역할이 있겠지만, 문화 평론가인 앤디 크로치(Andy Crouch)는 이렇게 말한다. “우리는 정치 기구들이 혼돈의 심연으로부터 우리를 영원히 구해줄 것이라는 희망을 버려야 한다.” 요즘 북한 정부는 남쪽으로 풍선을 날리지 않는 것 같다 (이맘때의 날씨도 풍선을 날리기에 좋지는 않다). 그러나 그들은 여전히 일본과 미국에 기습공격을 감행하고 있다. 평화협상 과정이 무산될 것이라는 두려움도 없이 말이다. 이처럼 남쪽에 사는 우리도 북쪽으로 날리는 전단들이 우리를 전쟁 직전으로 몰고 갈 것이라는 걱정을 하지 않아도 될 것이다. 대신, 우리를 훨씬 더 괴롭히는 무언가를 걱정해야 한다. 질문은 이것이다. 한국전쟁이 끝나고 65년이 지났건만, 우리 스스로 평화를 이루려는 노력과 방법, 심지어 이산가족 문제까지도, 그것들을 처음부터 우리에게서 앗아간 정부에게 맡기지 않는 법을 아직도 배우지 못했으니 말이 되는가?

Balloons for peace, why do we have balloons in North Korea?

Launching balloons into North Korea is never boring work, but these are especially interesting times to be a launcher. “Why can’t you just wait to launch?” is the question one hears repeatedly, often urgently and in frustration, asked by government officials, police, media, Facebook commenters, and even friends. Are you bigger than the peace process? Are you blind to the risk to which you are subjecting all of us? Are your partisan goals more important than everyone’s peace? The Ministry of Unification is allegedly even offering support to at least some launchers to switch to other human rights activities, ones that the MOU judges don’t violate the spirit of the recent peace summit so egregiously. Everyone seems moved by the spirit of healthy compromise and mutual respect these days—everyone, that is, except for balloon launchers.

I certainly can’t speak for all balloon launchers. My organization, Voice of the Martyrs Korea, is indeed one of the “big three” launchers by volume of materials launched, but we have little in common with other organizations which launch balloons. We launch only Bible portions, not human rights flyers. We use the version of the Bible published by the North Korean government, which the North Korean government insists can be read legally by all North Koreans, as according to the North Korean constitution. We always announce our launches to the police but never to the media. We launch only at night and in remote, unpopulated areas. We use expensive cutting-edge technology to make sure our balloons and Bibles make it safely and unobtrusively into North Korea—everything from advanced computer modeling to GPS tracking to tiny weather balloons that are too small for radar and that pop without a trace rather than landing; and, beginning this year, helium gas only, not the more controversial (though far less expensive) hydrogen.

And clearly the balloons are having an impact. North Korea Human Rights Records Preservation House’s “2015 White Paper on Religious Freedom in North Korea” reports that the number of North Koreans who saw a Bible while in North Korea increased from near 0% in the year 2000 to 7.6% by 2014. That’s certainly not only due to our balloon Bibles; after all, Voice of the Martyrs Korea and other organizations get Bibles into North Korea through a host of other channels. But all those other channels combined don’t add up to anywhere near the impact of the 40,000 Bibles we’ve launched annually for more than a decade.

Still, it’s more than understandable to ask: Should a peace process be risked just so Christians can proselytize and North Korean defectors can protest? Freedom of expression and freedom of religion are important values, but are they so absolute that they can trump (no pun intended) compelling national interests?

This is the way the debate is typically framed, and thus it is no wonder so few would side with the balloon launchers. Yet, is it possible that the real problem is with the framing of the debate itself?

To ask, “Can’t you just wait to launch?” is in essence to ask, “Why can’t you respect and trust the peace process?” But it is possible to sincerely respect a peace process between governments and behave honorably towards it, without having our own understanding and practices of peace limited by it.

Put differently, peace is too important and too big to be arrogated solely to governments. There is a kind of peace that can be manufactured when those south of the DMZ line up behind President Moon and those north of the DMZ line up behind Kim Jong Un and no one jumps the queue. But it is a pre-processed, institutionalized peace, with government-supplied flags, photos suitable for social media, and sporting and cultural exchanges to build the kinds of relationships with which governments are comfortable, at the pace with which they are comfortable. It is peace via four-point declaration. Historically, peace by declaration is frail, anemic, and contrived, usually found on life support, and always needing force to protect and preserve it.

By contrast, we need only recall the images of people climbing over the Berlin Wall to remind ourselves that true peace among a divided people typically breaks out in a human flood, not a declaration, and government’s role in the process is not to originate, achieve, define, schedule, and orchestrate it but rather to simply stop holding it back. It is not a shared love of sport and culture that draws the two Koreas together at the deepest level, nor is it the allure of a trans-Asian railroad, nor even a joint aversion to war. It is, quite simply, Koreanness. The peoples of these countries do not need to be chaperoned in their interactions, or even re-introduced. Despite the estrangement of the young, enough natural ties still remain such that were the governments involved simply to pledge not to blow anybody up, ordinary Korean people would instinctively know a surprising amount about how to initiate the core processes required to power the lengthy, difficult, and expensive work that lay ahead. It’s one of the benefits of a Confucian culture, and one of the generally true things about human beings once artificial (i.e., government erected and maintained) barriers are removed.

This is not a naïve proposal to achieve peace by “tearing down that wall” (though, interestingly, there may be more historical precedent for that than for the kind of peace process envisioned by the Panmunjom Declaration). Instead, it is an observation that one can sincerely respect governments’ roles in peacemaking by doing something more and other than standing down and deferring to governmental efforts. In fact, one shows respect by doing one’s one part for peace, making one’s unique contribution—whether governments like it, understand it, or can fit it into their own process.

Instead, this article is a declaration that it is possible for people to sincerely respect governments’ roles in peacemaking by doing something more than just supporting the governments’ efforts. People can (and should) be involved in different ways of making peace other than the ones that the governments are doing. We should not just wait around for government to tell us how to be involved in their peacemaking process. In fact, the way we can be most respectful toward the overall goal of peace is for each of us to make our own unique individual contribution for peace. Governments may or may not like our contribution. They may or may not understand it. They may or may not be able to fit it into their own peacemaking process. But that is fine.

Authentic peace is not a spectator sport, not a one-track effort, not an orderly three-act play. It is not so much negotiated by governments as it is recognized by them; that is, peace breaks out, not altogether differently than how war does. As war represents the simultaneous parallel failure of many societal organs, peace represents their simultaneous parallel renewal beyond any of one of their singular control or orchestration. Each organ has a distinct and concurrent role to play in peacemaking, and part of any peace process is being cognizant of the inability of any one organ to make it happen or even to lead it, humble enough to accept that, and wise enough to make sufficient space for it. Christians would say peace comes in God’s time, and rarely through official channels. But regardless of one’s faith background, history reveals that peace somehow happens across a society, not from the top down; no one gets to run the thing, not even the presidents.

In the case of Voice of the Martyrs Korea, we launch Bibles not in an effort to proselytize for Christian converts but rather as our contribution to the peace process: We support North Korean underground Christians’ efforts to foster a different calculus for the valuing of individual human life in North Korea. According to the BIble, one is human (and deserves humane treatment) not because one is loyal and useful to the government but simply because one is created in the image of God—an inalienable state which can’t be granted by governments nor withheld by them. We have carefully launched this message (a North Korean message, translated by the North Korean government and protected by the North Korean government) into North Korea for more than a decade. With full submission to the laws (and punishments) of South Korea we have launched this message even through the death of Kim Jong Il, the sinking of the Cheonan, and the bombardment of Yeonpyeong. These launches have yet to start a war or derail a single step towards peace. The Bibles reaching ordinary North Koreans, however, brought meaning, forgiveness, and, yes, peace to many hearts, as our diverse and far-flung network inside and around North Korea can readily attest.

Christians may have a different vision of peace than governments, but it would be passing strange for a governmental peace process to be strengthened and safeguarded by snuffing out parallel peaceful efforts—including, I might note on behalf of other launchers, peaceful protest, which has historically contributed at least as much to the restoration and maintenance of peace in civil societies as have sports and cultural exchanges and blueprints for intercontinental railroads. The content of the flyers of these other launchers may on occasion be bombastic or crude, but to describe the flyers as “anti-North Korean”, as many purportedly neutral global news outlets regrettably are, is to make the egregious error of identifying all North Koreans as one with their leader, thus politicizing them. This politicization of inter-Korean relationships is arguably the very thing that stands as the greatest impediment to peace (or, at least the overcoming of that politicization offers peace the greatest hope for success).

Balloon launchers launch in order to overcome the barriers to direct communication between ordinary Koreans that continue to be maintained by the governments of both Koreas. Ordinary Koreans did not erect the DMZ. Governments did. The DMZ is not the product of ordinary Koreans mistrusting each other. It is the product of ordinary Koreans trusting governments too much, and entrusting them with too much; namely, the DMZ reflects the politicization of the relationships between ordinary Koreans. A peace process that retains that politicization, even in reconfigured form—i.e., with North Koreans and South Koreans interacting with each other as North Koreans and South Koreans through carefully controlled and choreographed events and exchanges—is, at worst, doomed to fail or, at best, certain to be overtaken at some point by Koreans insisting that peace means the unmediated ability to interact with each other simply as Koreans, human beings, and families. “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall/ That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,” wrote Robert Frost. The frozen ground swell of a human rights balloon flyer is sometimes not pretty, but it beats a wall—especially if the wall is keeping you away from those you love on the other side.

Governments have their part in making peace, but we must be careful not to permit them to monopolize our means of making peace and of interacting with each other—either before, during, or after their periodic peacemaking efforts. Governments have their part in making peace, but as cultural commentator Andy Crouch notes, “We no longer need to invest our political structures with hopes of eternal rescue from the abyss of chaos.” The North Korean government may not be launching balloons southward these days (the weather would not permit it this time of year anyway), but they continue to launch salvos against Japan and the United States without fear of derailing the peace process; those in the south should be similarly comfortable that we needn’t worry too much about north-bound flyers propelling us back to the brink of war. Instead, we should worry about something far more vexing: Is it possible that after 65 years, we still haven’t learned not to cede our peacemaking efforts and imaginations and even familial relationships to the governments that took them away from us in the first place?